University of California, Riverside

UCR’s complicated history with the

Last Great Western Manhunt

Two movies have been made about the sad saga of Willie Boy, and three books written. There is a story within the story of what’s been called “the last great Western manhunt.” That is, why are there so many different versions of the same historic event?

I n 1909, a tragic episode occurred around Banning, California, that had — or was made to have — intonations of Romeo and Juliet. It was called “the last great Western manhunt,” and it followed the killing of a respected tribesman by a lovestruck young American Indian named Willie Boy. It has been framed as a grand tale of a fast-withdrawing world, with a fugitive — said to be from a legendary cult of “Indian runners” — who covered 600 miles in strides of up to 7 feet in length during his pursuit.

UC Riverside is effectively the keeper of the Willie Boy manhunt’s history. UCR’s Rivera Library holds 16 boxes of Willie Boy archives and artifacts. The two Hollywood movies that have come of the Willie Boy saga — released in 1969 and 2022 — are heavily influenced by three books written by authors with UCR affiliations.

For much of its history, the story was told through the lens of “the frontier myth,” which morphed the last manhunt into a story of civilization over savagery — though Willie Boy was known and respected by white ranchers as a hard worker, fluent in English, and a sharp dresser.

UCR’s Rivera Library holds 16 boxes of archives from the Willie Boy manhunt. They include the scrapbooks of Riverside County Sheriff Frank Wilson, photographs, newspaper clippings, and three-dimensional artifacts including the can posse members said was found with Willie Boy’s body at Ruby Mountain. (UCR/Stan Lim)

But by 1909, the area of Southern California around Banning was far divorced from the frontier, or the “Wild West.” Reservations existed and American Indians intermingled with whites with varying degrees of assimilation. There were still tensions, many tied to land and boundary disputes as reservations were created. But they played out in the courtroom rather than on the battlefield.

There is a basic framework to the Willie Boy story upon which all agree. Willie Boy and his beloved, Carlota Mike, eloped but were soon “captured” by family members and brought back home. The Mike family — incorrectly named “Boniface” in many accounts — moved for work to the Gilman Ranch in Banning, and Willie Boy followed. Willie Boy confronted and killed William Mike, Carlota’s father and chief of the Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indians, and fled with her into the Mojave Desert, covering as much as 50 miles in a day and 600 miles overall. A manhunt involving four different posses pursued them. Carlota was killed. After her death, there was a dramatic shootout during which Willie Boy felled several horses from a high vantage point.

What happened next to Willie Boy is one of many points on which the stories diverge.

The two movies made about the last Western manhunt, both of which employed UCR researchers as primary sources, include 1969’s Robert Redford film “Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here,” and 2022’s “The Last Manhunt,” made by actor Jason Momoa’s production company. The movies were left to sort — or perhaps disregard — fact vs. fiction from published accounts.

The 1909 Madison Version

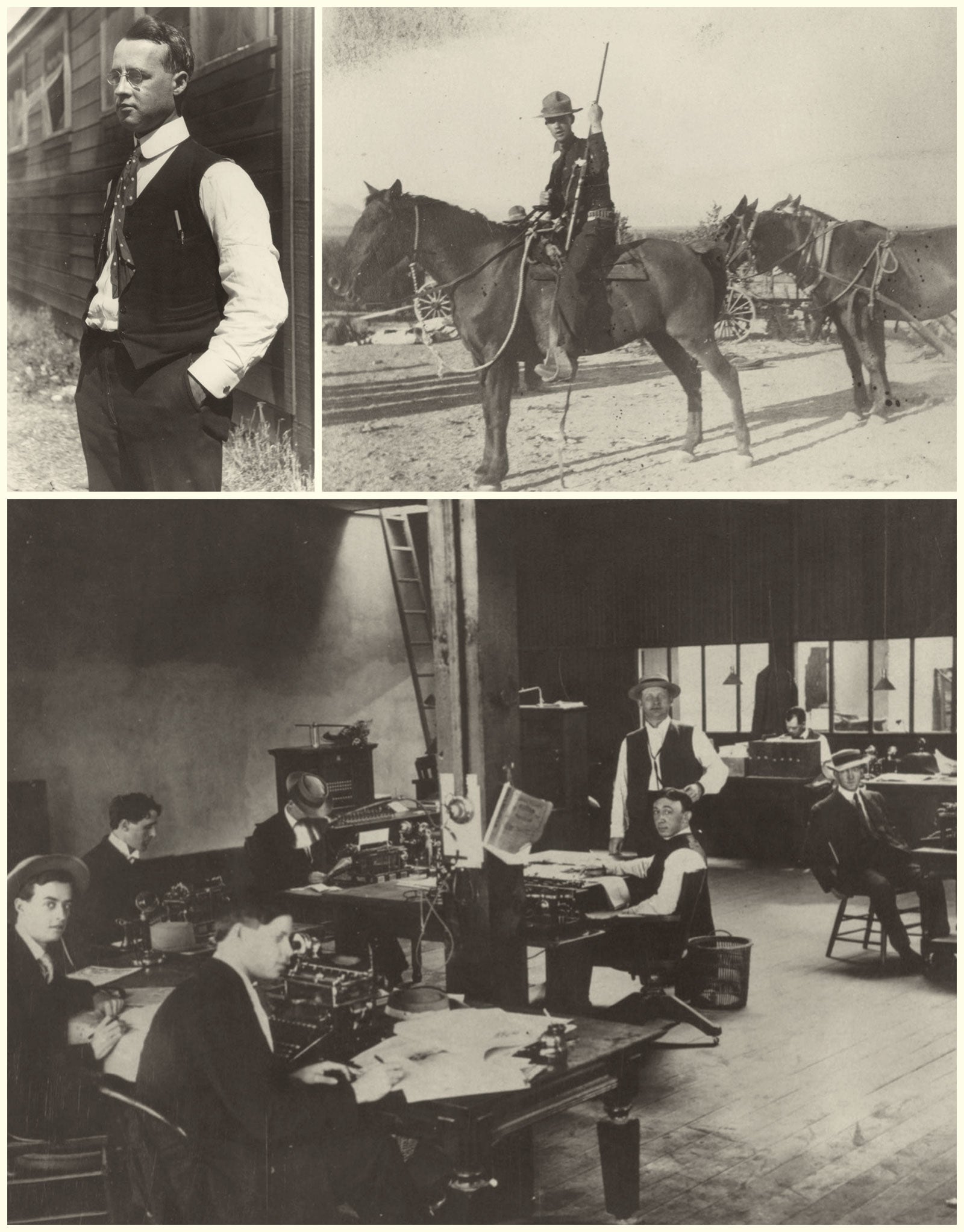

The flawed history upon which the two movies are based hails to the original telling by a cadre of journalists that included 22-year-old Randolph Madison, who accompanied a posse on its last leg, and which was influenced heavily by Riverside deputy sheriff Ben de Crevecoeur, whose family had been displaced by the Malki Indian Reservation. Many of the stories have no bylines and would have passed through the hands of multiple rewrite men bent on selling newspapers.

Newspapers in Riverside and San Bernardino counties, including Madison’s Banning Record as well as the Redlands Daily Facts, Redlands Daily Review, the Riverside Morning Mission, and the San Bernardino Daily Sun, sensationalized the accounts, portraying Willie Boy as a drunkard and in the most villainous light.

Randolph Madison — a distant relative of President James Madison — was the lone reporter to accompany the posse at Willie Boy’s alleged last stand, with camera in tow. In a photo of the Los Angeles Record office, taken on the day his Willie Boy story broke, Madison can be seen at the far left. Many of the photos from the manhunt were provided 50 years later to the author Harry Lawton by Madison’s widow. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

Madison’s and other newspaper accounts hold that William Mike was shot while sleeping by a drunken Willie Boy, who was identified as a Paiute Indian; he was later found to be Chemehuevi and Southern Paiute. Carlota was subjected to “marriage by capture” by Willie Boy, who kicked and beat her, “mistreating her horribly.”

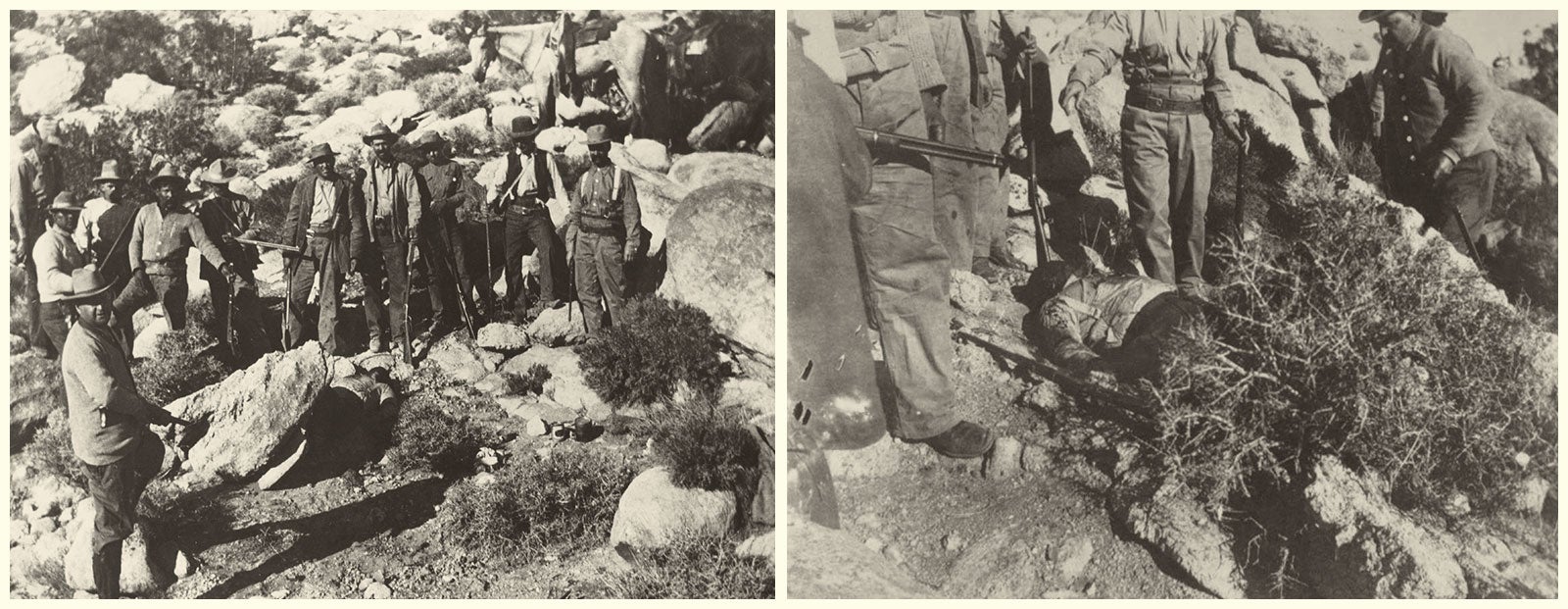

The newspaper accounts assert that Willie Boy shot Carlota in the back, tired of her lagging. Willie Boy later returned to the site of her killing and squared off with a posse at Ruby Mountain, shooting and killing three horses and wounding posse member Charlie Reche. A lone shot was heard as the posse retreated with the wounded Reche, which the posse came to believe was a suicide discharge from Willie Boy’s rifle, according to the accounts. The posse described discovering his body several days later, bloated by days in the desert sun.

In a seven-page transcript of Madison’s final manhunt story, which lives in the UCR archives, Madison writes: “Unable to carry the body back to civilization, over the rocky torturous road we had followed from Banning it was determined to cremate the remains on the spot where Billy (sic) Boy fought his last battle. Wood was heaped over the body as the flames quickly reduced the body to a heap of ashes which will be scattered to the winds at first breeze.”

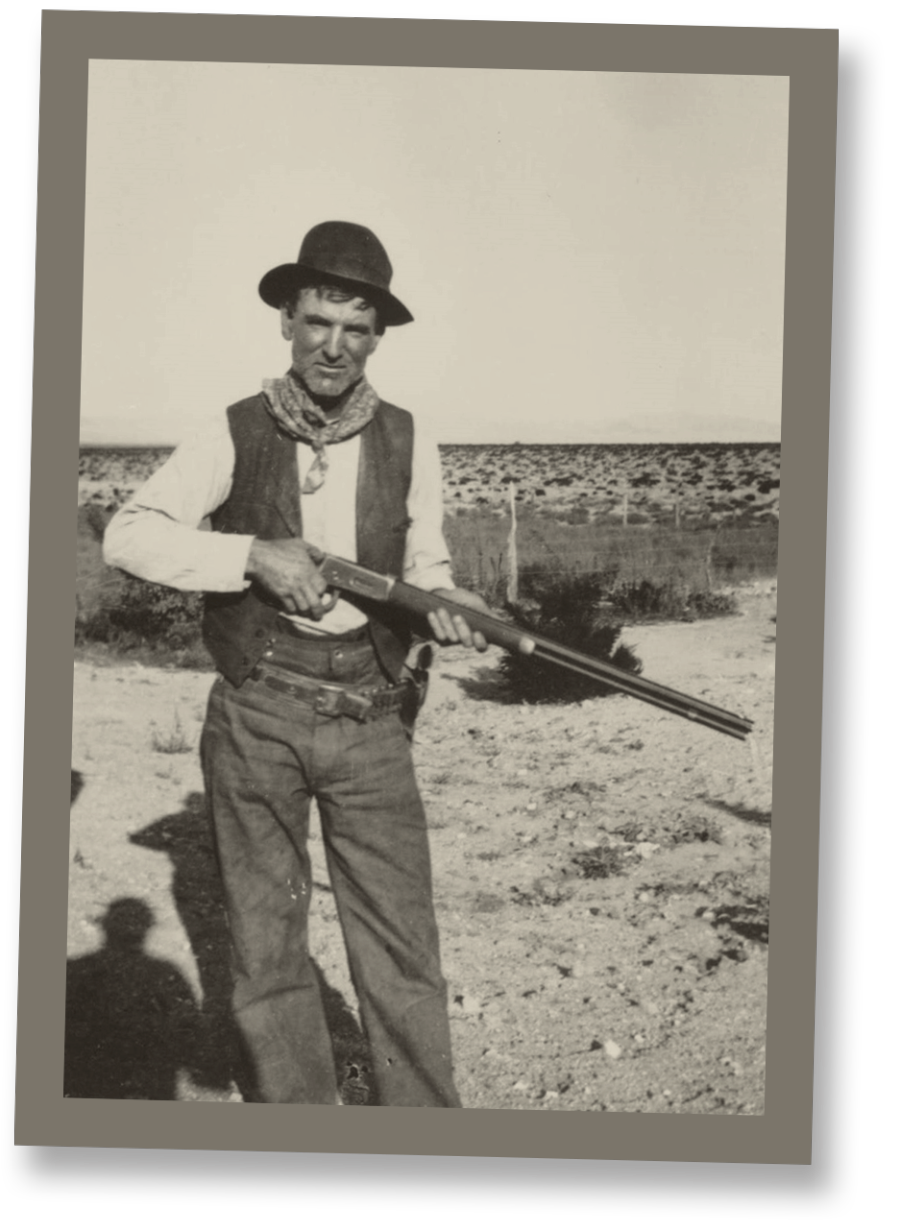

1909 newspaper accounts assert that Willie Boy died by suicide, using his last bullet after fending off a posse at Ruby Mountain. The posse retreated from his assault, returning several days later to find Willie Boy’s body. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

The newspapers fashioned a tie-in between the manhunt and an unrelated visit to Riverside by then-President William Howard Taft. The reporters on Taft’s campaign trail found the president’s tour ho-hum, and so thought to intersect with the manhunt drama. Would the crazed Willie Boy attempt to kill the president? The newspapers insinuated American Indians were aiding Willie Boy in his flight, and that an American Indian rebellion was afoot. With episodes in recent memory including Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn in 1876 and the 1890 uprising at Wounded Knee, it had the effect of stoking readers into a frenzy.

“Willie Boy”

The 1960 book “Willie Boy: A Desert Manhunt” was the first extended retelling of the story following the 1909 newspaper accounts. It was written by Harry Lawton, who worked at UCR from 1965 to his retirement in 1991 as a writer, editor, administrative analyst, and management services officer in the College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences. In his 2006 LA Times obituary, Lawton is credited with founding and chairing the university’s creative writing program and founding its ongoing annual Writers Week event.

In 1958, a few years before he joined UCR, a young Harry Lawton surveyed the scene at Ruby Mountain where Willie Boy ambushed a posse. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

Lawton would come to call his book “historical nonfiction,” borrowing from Truman Capote’s later characterization of “In Cold Blood.” It’s the lone literary telling of the story, offered in Lawton’s elegant prose, and it was based in part on the account of the last surviving posse member, Joe Toutain.

Lawton’s correspondence in the UCR Library includes back-and-forth exchanges with publisher Horace “Doc” Parker, who repeatedly penned misgivings about the original source material. Parker wrote that the 1909 newspaper stories were “very much embellished” based on his own research and declared the primary newspaper source, deputy sheriff and posse member de Crevecoeur “as windy as a cow on green pasture.” Parker also had misgivings about Carlota’s death. Isn’t it more likely she was hit by a stray bullet from the posse?

But Lawton’s telling ended up being largely true to the newspaper accounts. A drunk Willie Boy kills a sleeping William Mike and forcibly takes Carlota. Willie Boy later kills Carlota.

Lawton introduced a controversial flourish of literary license. He refers to Carlota as “Lolita,” summoning Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita,” a novel that involves a relationship between a middle-aged man and a 12-year-old girl. In reality, Willie Boy was 28 and Carlota 16.

There is at least one reference in Lawton’s papers to an alternate ending — that Willie Boy escaped and lived out his life into the 1930s. This became a point of focus for a later UCR Willie Boy chronicler, Cliff Trafzer.

But a letter in Lawton’s files from Randolph Madison’s widow, Christina Somerville (Madison) Wagner asserts: “I am sure that the body was that of Willie Boy. I know Mr. Madison believed it to be him and in discussing the story, he told how badly the body was swollen and that they had no choice in disposing of it.”

The book won the 1960 James D. Phelan Award for nonfiction, was in time released in the lucrative paperback market, and later adapted into Redford’s “Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here.”

Lawton was placed in a defensive posture in later years by a subsequent book that countered many of his claims. Lawton in turn asserted his ties with the local American Indian community, including helping found the Malki Museum on the Morongo Indian Reservation, the first American Indian museum on a California reservation. Lawton also helped start the nonprofit Malki Museum Press.

In Lawton’s 2006 obituary, the author’s son, George Lawton, said: “Keep in mind, my father’s book is a novel, not an exact historical account, but he spoke to eyewitnesses and was careful to get the facts. He didn’t say anything he couldn’t back up.”

“The Hunt for Willie Boy”

In 1996, Jim Sandos, a University of Redlands professor, and Larry Burgess, an adjunct professor at UCR and a librarian at the Redlands Library, published “The Hunt for Willie Boy: Indian-Hating & Popular Culture.”

Their book was based on oral interviews and represented the first scholarly assessment of the manhunt. Sandos and Burgess challenged the original newspaper accounts, and by extension, Lawton’s book and the subsequent Redford movie. The authors asserted that Lawton’s publisher, Parker, lamented that he wished he had written the tale of Willie Boy himself.

Sandos and Burgess strenuously questioned newspaper accounts of Willie Boy’s drunkenness, which were based on de Crevecoeur’s narrative. “Now the story was complete. Demon drink had unleashed Willie Boy’s lust and permitted him to act upon his base impulses,” the authors wrote facetiously, asserting no proof of alcohol consumption was ever offered. “Alcohol had effectively uncorked the evil that lurked inside him.”

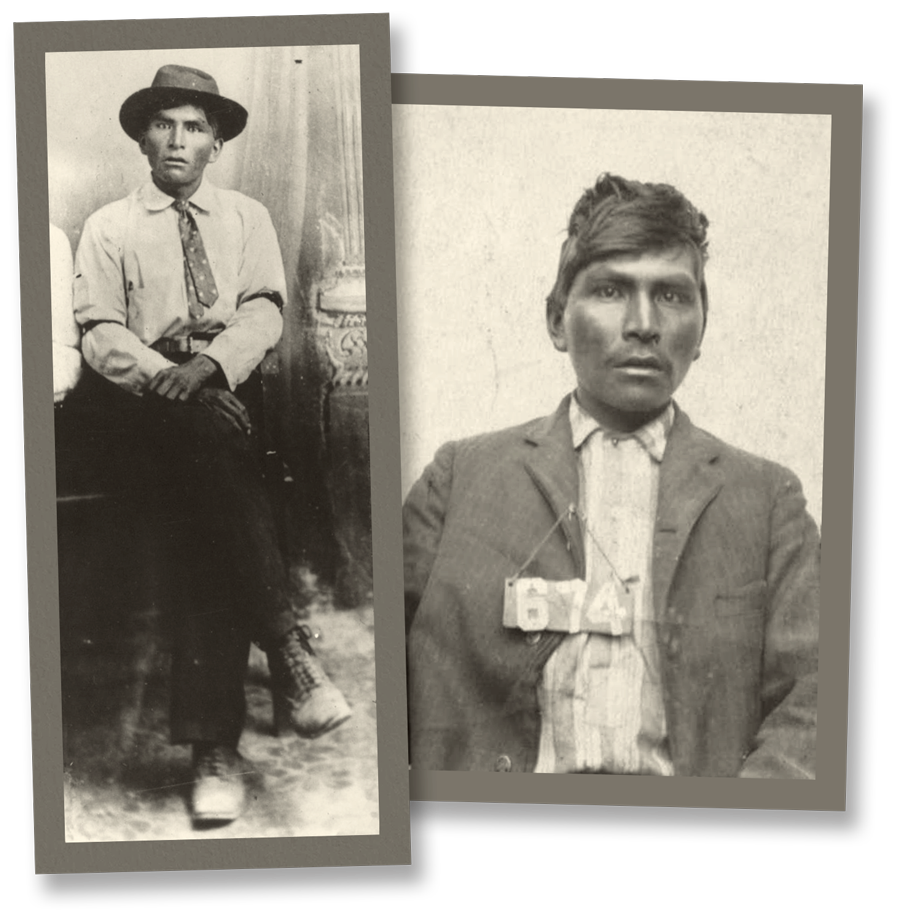

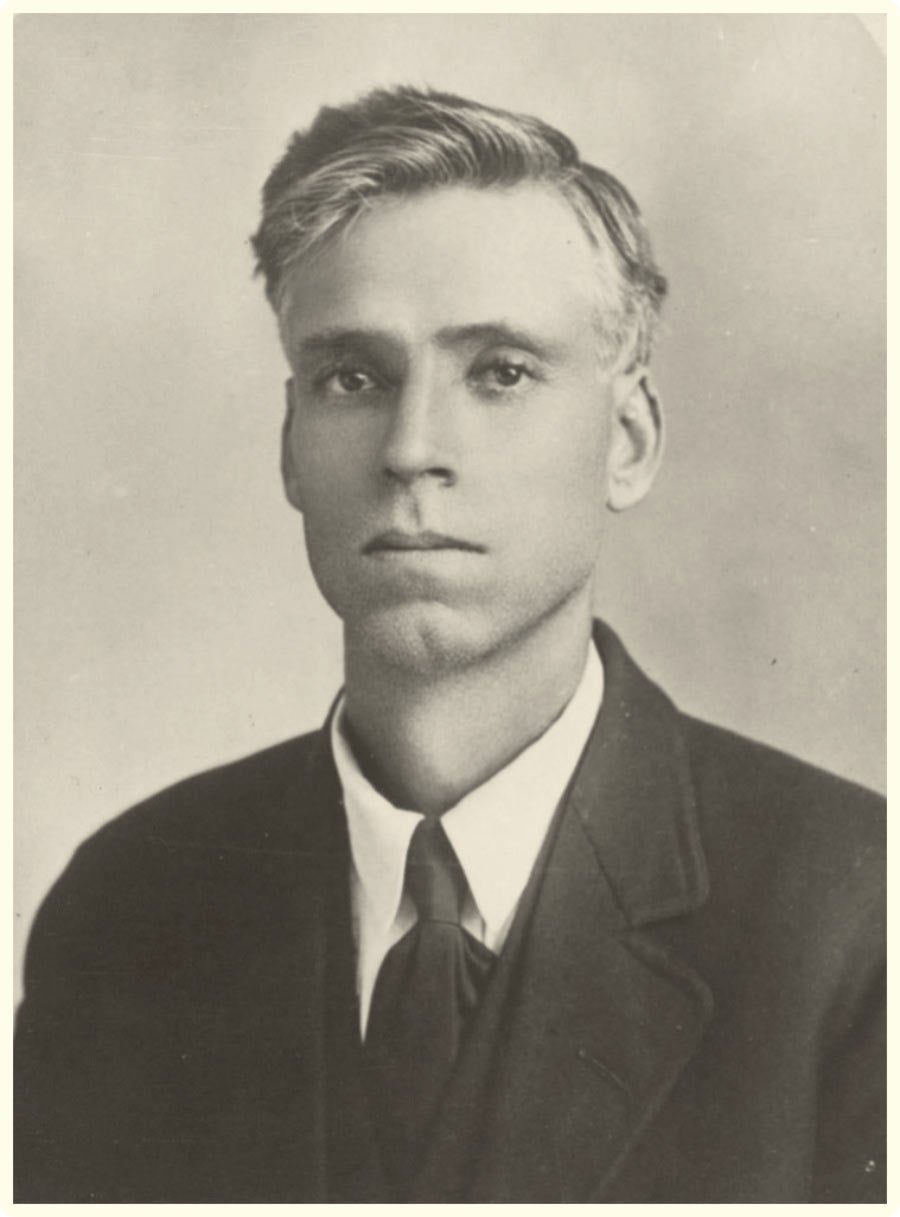

Willie Boy had served 90 days in a San Bernardino jail for disturbing the peace in 1906, but this was reinterpreted by newspaper accounts as an episode of drunkenness. In fact, the charge was applied to many offenses at that time, ranging from bicycle theft to murder. Willie Boy was known to be something of a dandy, dressing well and once paying to have a photographic portrait taken. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

The authors tied Willie Boy to a band of tribal messengers. Oral tradition held the messengers were renowned for carrying dispatches in superhuman strides and with little water. The secret involved not magic, but methods of body and mind control. “We provisionally conclude that Willie Boy must have been a runner in the old Chemehuevi tradition,” Sandos and Burgess wrote.

The authors surmise that one of the American Indian trackers — the trackers would have been at the front of the posse — shot Carlota, and that they obfuscated the true nature of her death, including from other posse members. This assertion wins some support from the coroner’s report, which held the cause of death was “gunshot wound in the back fired by party to the (coroner’s jury) unknown.” One of the members of the posse, Joe Knowlin, was among the coroner’s jury members, which the authors believe suggested that posse members suspected Willie Boy didn’t shoot her. But the posse didn’t want to alienate the trackers by opening an inquiry.

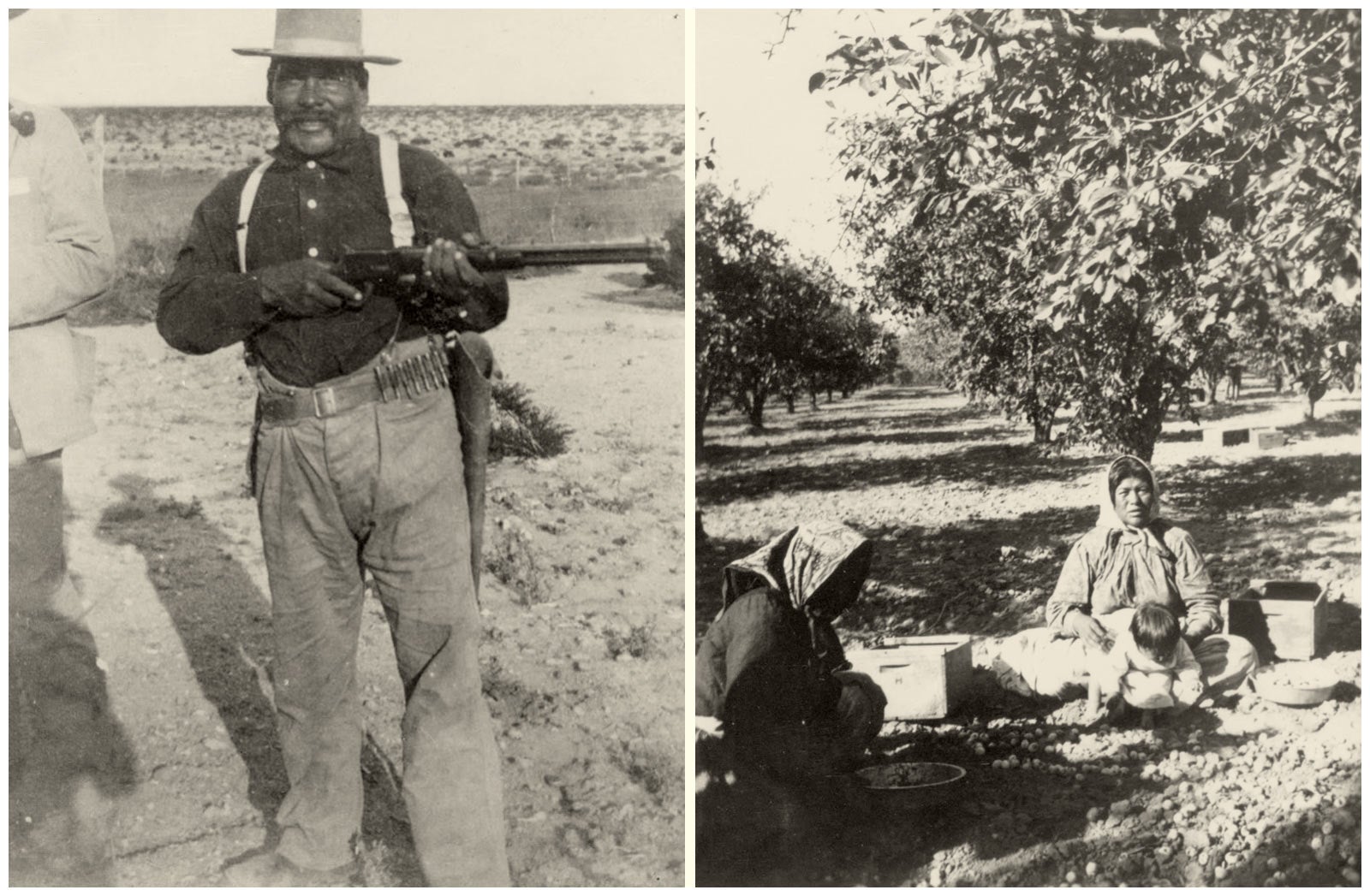

Posse member Joe Knowlin, identified on the reverse of this photograph as “a dead shot,” was a member of the coroner’s jury, which declined to identify Willie Boy as Carlota’s killer. This led authors Sandos and Burgess to conclude that the posse may have suspected one of its own members shot her. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

There is a major plot point in the newspaper account upon which Sandos and Burgess concur, that Willie Boy killed himself.

Lawton vociferously objected to the Sandos-Burgess book’s characterization of his own book, going so far as to file a lawsuit. The suit was settled with an agreement that a notecard would be placed inside each subsequent book, asserting that “Harry Lawton is not an Indian-hater,” and that Parker — though he would have liked to publish his own Willie Boy account — had confidence enough in Lawton’s version to publish it.

“Willie Boy and the Last Desert Manhunt”

Cliff Trafzer, a UCR distinguished professor of history, published in 2020 “Willie Boy and the Last Desert Manhunt,” which introduces a fundamental shift from the traditional telling. In Trafzer’s version — based on oral histories shared with him by the tribes — Willie Boy escaped and lived out his life in Nevada, dying of tuberculosis many years later.

Trafzer was born to parents of Wyandot Indian and German blood and is the university’s Rupert Costo Chair in American Indian Affairs. He agrees with Sandos and Burgess’ telling on many points, including that William Mike objected to the Willie Boy-Carlota union because they were cousins, and not because of their age difference. According to Chemehuevi and Paiute tribal marriage and incest laws, cousins had to be six generations apart to marry.

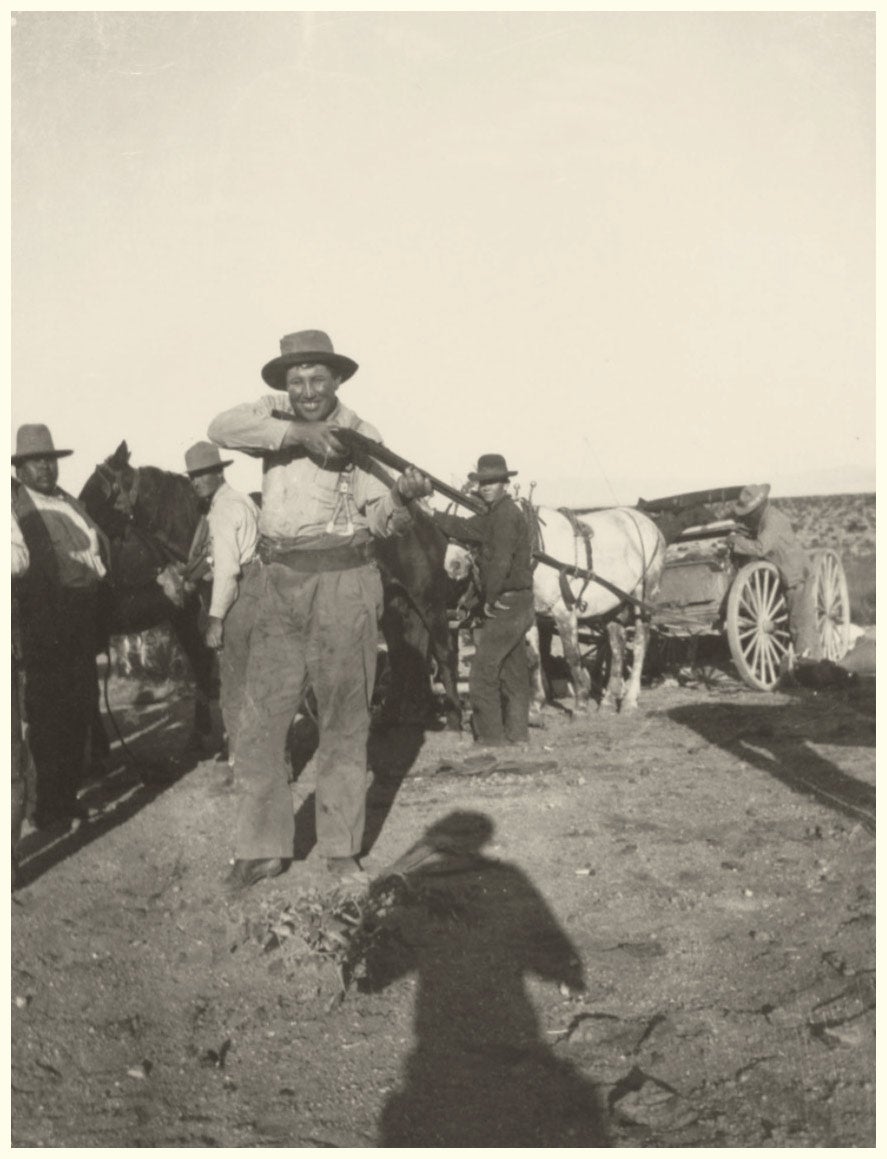

Posse member Charlie Reche, who was wounded by a bullet from Willie Boy’s rifle at Ruby Mountain. Trafzer maintains Willie Boy intended to shoot the horses and not the lawmen, and that Willie Boy had plenty of opportunity to finish off Reche, as he lay in the open for several hours. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

Carlota insisted Willie Boy get her father’s permission before they eloped a second time, Trafzer asserts. The book offers that Willie Boy brought a gun — taken from his employer, the rancher Arthur Gilman — to his meeting with William Mike out of fear, and that a struggle for the gun followed during which William Mike was accidentally shot.

Trafzer maintains that Carlota was shot by the American Indian tracker John Hyde from a distance, with Hyde having mistaken her for Willie Boy as she was wearing Willie Boy’s coat.

“I base my interpretation of a posse member killing her by mistake on the coroner’s report showing it was a long-distance shot entering her shoulder/back and exiting below her stomach,” Trafzer said. “Why would Willie Boy, who loved Carlota, kill his wife? Makes no sense to me.”

He is less charitable toward the posse’s knowledge of Carlota’s death than Sandos and Burgess, asserting: “At some point, the posse agreed to shift the blame for Carlota’s death from the posse to Willie Boy.”

The version surmises that Willie Boy left Carlota to get more supplies, then returned to Ruby Mountain and found her missing. Enraged, “he planned to put the posse on foot in the heart of the Mojave Desert,” believing he could best them in the desert if they weren’t on horses.

Trafzer made several arguments against Willie Boy having died by suicide, based in part on oral histories. These arguments include the fact that Madison “failed to take the kind of closeup photographs seen in other photographic presentations made by Western lawmen to unmask the desperado.” The posse would have been motivated to prove it had found Willie Boy, and would have brought him back to town, as was then the frequent custom. Also, Trafzer asserts, there is little fuel near Ruby Mountain with which to cremate a human body.

Trafzer said that he holds the opinion of the Chemehuevi and Southern Paiute people he interviewed: A “body” was staged for Madison’s photo.

Trafzer’s book maintains posse member and tracker Segundo Chino, pictured left, would later declare Willie Boy was not killed by the posse. Chino went on to marry Maria Mike, the widow of William Mike. Maria is pictured right with her daughter, Dorothy, following the deaths of her husband and Carlota. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

“Indians far and wide believe that Willie Boy survived the gunfight on Ruby Mountain and lived out his life in Southern Nevada,” Trafzer wrote, citing sources in Nevada, California, and Arizona. Further, Trafzer said the American Indian tracker Segundo Chino told Cahuilla scholar Katherine Siva Saubel — with whom Trafzer spoke — that the posse never found Willie Boy.

Trafzer takes care not to disparage the book written by his onetime faculty colleague, but Trafzer said that Lawton “refused to listen to oral histories.”

“Tell Them Willie Boy is Here”

Lawton shied away from identifying heroes and villains, but the movie based on his book didn’t. Universal Pictures optioned the movie, which was a comeback for director and screenplay writer Abraham Polansky, who had been blacklisted during the Joseph McCarthy era. The movie starred Redford as “Coop,” a composite of several sheriffs. The posses are likewise compressed from the actual four to only one.

In Polansky’s “Tell Them Willie Boy is Here,” Willie Boy — portrayed by Italian-American actor Robert Blake — is a cocky, brawling, drunken womanizer, which loosely follows the newspaper narrative. But on most points, the telling strays widely from both the newspaper and Lawton versions.

In the Hollywood version, William Mike wields the gun and is killed after Willie Boy wrests it from him. Carlota is “Lola,” portrayed by American actress Katharine Ross, whose skin is darkened with bronzing products. Lola is slain by Willie Boy in a sort of ritual killing — laid out in a white dress. Blake’s Willie Boy is gunned down when he squares off with Redford’s Coop, after which Coop discovers there were no bullets in Willie Boy’s gun.

In the 1969 movie “Tell Them Willie Boy is Here,” Willie Boy was portrayed by the actor Robert Blake, who would go on to play 1970s detective “Beretta,” and who would later in life become embroiled in a murder scandal of his own. Katharine Ross, pictured right, was Carlota, named “Lola” in the retelling. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection/Universal Pictures)

Robert Redford played the brooding, fictitious sheriff “Coop,” who spends much of the movie navigating a contentious and lustful courtship with the fictitious Indian agent Elizabeth “Liz” Arnold, portrayed by Susan Clark, as seen on the right. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection/Universal Pictures)

Polansky intended the movie as a commentary on the U.S. political climate of the late 1960s, with the destruction of Vietnam paralleling the destruction of American Indian culture at home.

The movie, which won some critical acclaim, was viewed at the time as sympathetic to Native Americans, and there is not a record of strenuous pushback from the tribes of the region. It was filmed on the Morongo reservation and provided an economic stimulus to the tribe. Saubel, then president of the Malki Museum in Morongo and co-author of technical papers on the Cahuilla people, consulted on the movie. With a team of American Indian singers, she recorded background music and a song for one scene.

“The film took a different tack on the events. It told a story that was at once archetypal and mythic — a battle between two men: Willie Boy and ‘Coop,’ a fictional composite character who leads the posse. Willie Boy, an Indian despoiled by the alcohol of the civilized whites, is a classic outlaw in the style of James Dean,” wrote Julia Sizek for the Mojave Project. “Coop is a reluctant lawman who has the tools to defeat Willie but would rather leave the Indians to settle the case. The film builds during the prolonged chase — lawman and civilization against the somewhat noble savage — and the viewer is meant to feel conflicted while watching the Old West end as Coop kills Willie in a shoot-out deep within Pipes Canyon.”

Sandos and Burgess wrote of the movie that it “contributes to a preservation of the white version of the frontier and perpetuates Indian-hating.”

“The Last Manhunt”

Contrasted with the 1969 Willie Boy movie, 2022’s “The Last Manhunt” was low budget, featuring few “name” actors. Martin Sensmeier is Willie Boy, Mainei Kinimaka is Carlota, and director Christian Camargo is a boozy Sheriff Frank Wilson. Wilson was the real-life Riverside County sheriff but is a composite of several sheriffs in the film. Jason Momoa, who produced the movie and co-wrote the script, plays a bit part.

The movie portrays Willie Boy as a sympathetic character. Sheriff Wilson, while a grieving drunkard, is an honest man who wished to bring Willie Boy back alive. The reporter, Madison, is headline-hungry, and deputy sheriff de Crevecoeur is the villain of Momoa’s “The Last Manhunt,” obsessed with publicity and disliked by fellow posse members.

Riverside County Sheriff Frank Wilson gets a hero’s treatment in “The Last Manhunt.” (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

The movie favors the Sandos-Burgess and Trafzer assessments of Carlota’s death, pinning it on the tracker Jim Hyde, who is depicted as bent on killing Willie Boy because he brought shame to his tribesmen. The viewer is led to believe Willie Boy escaped, with his silhouette glimpsed atop a mountain by Sheriff Wilson in a closing scene. Trafzer, who was a consultant for the movie, said Momoa asked permission of the Mike family and the Twenty-Nine Palms Tribe to do the film and was given their consent.

“He and his team deserve high marks for seeking tribal permission,” Trafzer said.

Posse member Ben de Crevecoeur has been on the receiving end of progressively uncharitable depictions in books and movies about the Willie Boy saga. (UCR Library, Harry W. Lawton Collection)

The movie had a limited theatrical release. The critical response was tepid, though the sweeping desert cinematography won praise.

Trafzer’s UCR faculty colleague, Gerald Clarke, praises Trafzer’s effort to shift the Willie Boy narrative, but finds “The Last Manhunt” flawed.

“The Robert Redford movie and the recent Jason Momoa movie share one thing in common: They center on the white sheriff’s story, and actually minimize the story of Willie Boy,” wrote Clarke, an ethnic studies professor who is an enrolled member of the Cahuilla Band of Indians and lives on the Cahuilla Indian Reservation, serving on the tribal council. “There has always been a good bit of romanticizing of the Willie Boy story, making it out to be a local version of Romeo and Juliet. Until local tribal people have more of a say into how the story is told, I think we will continue to see Native American history used by the dominant society to understand itself.”