University of California, Riverside

Shining a Neon Light on Cyberpunk

A new exhibition from the Eaton Collection explores the history of cyberpunk and the genre’s continued evolution today

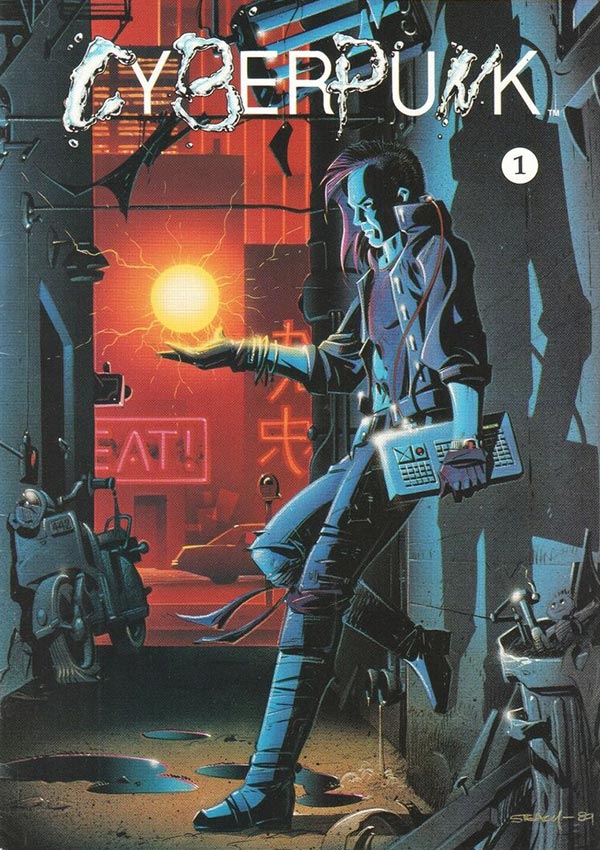

Upcoming from the Eaton Collection, “Neon in the Gutters: Cyberpunk Visions of the Future” will give visitors a close look at the world of cyberpunk through a selection of comics and graphic novels from the collection’s archives as well as displays exploring the genre’s connection to augmented and virtual reality, artificial intelligence, and body modification and cybernetics. Curated by Andrew Lippert, processing archivist in UCR Library’s Special Collections & University Archives, the exhibition is expected to open in early April. Here, Lippert shares more about the exhibition and the cyberpunk genre’s place in comics and popular culture.

What is “cyberpunk” and how does it distinguish itself from other sci-fi subgenres? How does it intersect with the sci-fi genre as a whole?

Cyberpunk is definitely a subgenre of science fiction. The early cyberpunk authors (examples include William Gibson, Rudy Rucker, Bruce Sterling, John Shirley, and Pat Cadigan) all came out of science fiction. There is always some debate whenever we start to define and categorize things, but I have settled on there being two main aspects that really stem from the term itself: the “cyber” piece and the “punk” piece. The “cyber” of cyberpunk is part of a long tradition within science fiction of imagining new technologies and new futures, or alternate worlds based on those technologies. In the case of cyberpunk fiction, it is taking the new technologies of the emerging computer/digital age of the 1980s and extrapolating those into imagined futures, often fairly cynical and dystopian. I think the “punk” piece is where cyberpunk really differentiates itself. It draws on the punk movement that began in the mid-1970s, borrowing the countercultural, underground, anticapitalist/anticorporate, and anarchist ethos. Many works of cyberpunk focus on characters from the margins of society fighting against some sort of powerful entity, often a corrupt globe-spanning megacorporation, but governments show up as bad guys, too.

What is the history of cyberpunk? When did it first become popularized?

The author Bruce Bethke is credited with coining the term when he titled his 1983 short story “Cyberpunk.” This term was picked up by Gardner Dozois, an editor and publisher, who started to popularize it. William Gibson’s novel “Neuromancer” (1984) is when it really burst onto the scene and started to gain widespread recognition, but there were other works in the first few years of the 1980s that squarely fit within the subgenre. These include “Software” by Rudy Rucker (1982), some short stories by Bruce Sterling, and Gibson’s short story “Burning Chrome” (in which he coined the term “cyberspace”). There are also some older works that are seen as predecessors to the subgenre, such as Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novella “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” The movies “Tron” and “Blade Runner” both came out in 1982 and are widely seen as works of cyberpunk and heavily influenced some of the early comics and graphic novels.

On the graphic novel side, I think Frank Miller’s “Ronin” (1983-1984) might be the first cyberpunk comic. In general, cyberpunk comics did not take off quite in the way that the prose fiction did. I have turned up about 10 or so comics and graphic novels from the 1980s and 1990s that I consider firmly in the cyberpunk subgenre. It is important to note that there were a number of Japanese manga creators working in a cyberpunk or cyberpunk-adjacent space during this time, too.

“Many works of cyberpunk focus on characters from the margins of society fighting against some sort of powerful entity.”

Was the rise of cyberpunk associated with, or in reaction to, any artistic or cultural shifts happening at the time?

There was a lot of advancement in computing in the 1970s, with the Commodore and the Apple II coming out in 1977. This transition from computers as niche and expensive devices to widespread commercial availability is what made cyberpunk happen. Blend this new technology with the countercultural elements of the nascent punk movement and you get cyberpunk in short order!

What are some notable cyberpunk comic titles explored in the exhibition?

One influential earlier work is the Japanese manga “Ghost in the Shell” by Masamune Shirow. It started in Japan in 1991 and was published in an English translation in 1995. It was notable for its storytelling and how it envisions future technologies. For example: the main character, Major Kusanagi, is a human brain/consciousness in a cyborg body. This will be in the exhibition.

There is a trio of comics from this early period that pioneered digital design and art tools: “Shatter” (1985) by Peter Gillis and Mike Saenz, “Iron Man: Crash” (1988) by Mike Saenz, and “Batman: Digital Justice” (1990) by Pepe Moreno. All three of these will also be in the exhibition.

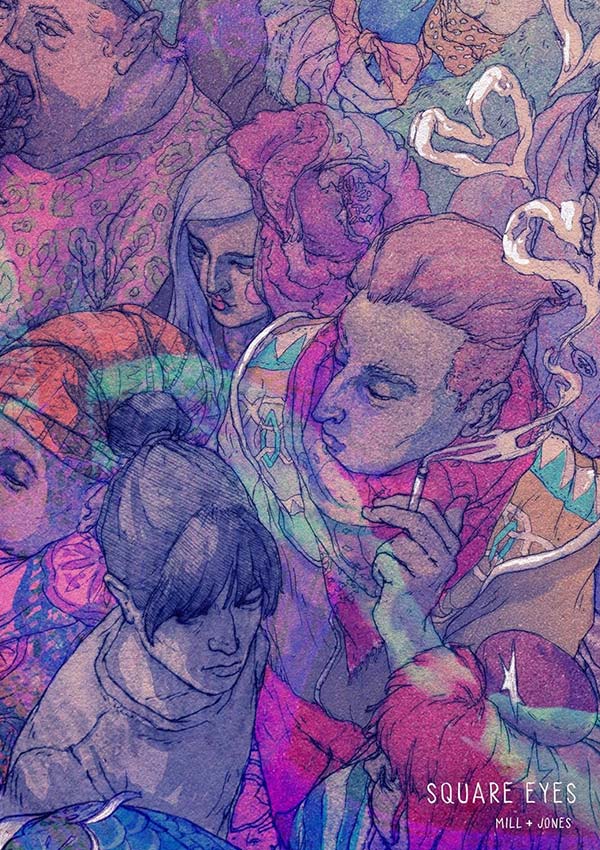

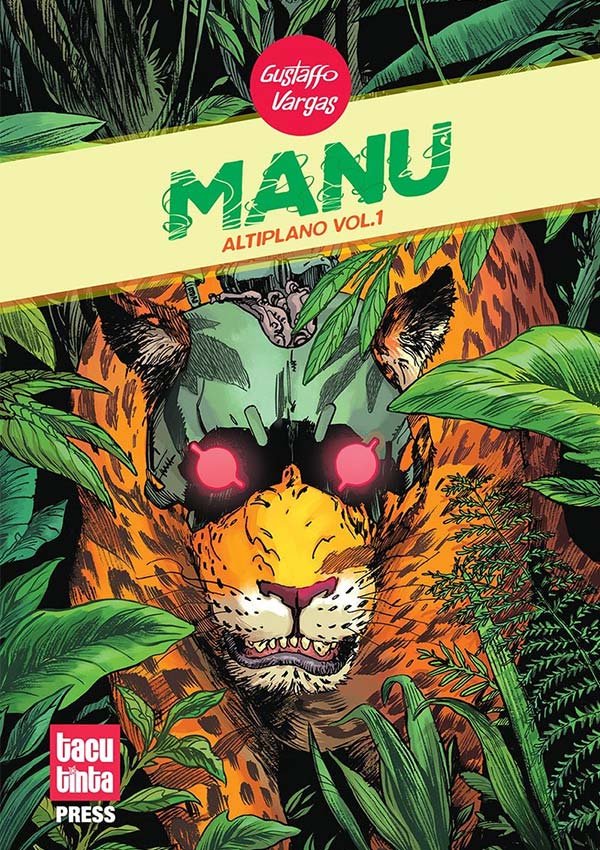

A variety of titles representative of the cyberpunk genre from the Eaton Collection will be explored in the upcoming exhibition. (UCR/Stan Lim)

Are there any specific themes or ideas within the cyberpunk genre you aim to highlight?

One major theme is the changing aesthetics of cyberpunk from when it emerged and solidified itself as a subgenre in the 1980s and 1990s, compared to somewhat of a reimagining in the 2010s and 2020s. Some of this is a result of changing design and printing methods and tools, but a big piece is the changing technological landscape over the last 45 years. Along with that, a new generation of comics creators have brought new visions and new ideas to engage with different aspects of a changing social and cultural landscape. I was struck by that aesthetic difference between the older and newer comics. Comics and graphic novels provide a space to explore graphically what prose authors can only describe via text, and there are a lot of fun visual representations of imagined future technologies and societies within a cyberpunk setting.

“Neon in the Gutters: Cyberpunk Visions of the Future” will be on view April to December in Special Collections & University Archives, located on the fourth floor of UCR’s Tomás Rivera Library. Exhibition hours are from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday.