University of California, Riverside

Reading Between the Panels

Screenwriter and professor Joshua Malkin shares his journey into the rich world of comic books

Alifelong fan of all things science fiction, fantasy, and horror, writer and UCR professor Joshua Malkin has dedicated his career to the genre. A screenwriter by trade, Malkin has written feature projects for Sony, Warner Brothers, Universal Pictures, and Lionsgate, among other production companies, and has taught screenwriting at UCR and the UCR Palm Desert Low-Residency MFA program since 2010. His professional interests have recently expanded into the realm of comic books and graphic novels, including writing the acclaimed comic series “The Source” with co-author Don Handfield. In 2021, the pair’s graphic novel “Unikorn” was optioned by Armory Films and is currently in pre-production. This February will see the launch of AMP Comics, a new independent comic label developed by Malkin, Handfield, and other partners, with Malkin serving as editor-in-chief. Here, Malkin shares more about his career, his journey into comic writing and publishing, and what makes comics so special.

Where did your interest in science fiction, fantasy, and other related genres originate?

Honestly, they were affections that were born, nurtured, and never shaken from childhood. They’ve been with me as long as I can remember — it’s just part of the nascent wiring, I think. In particular with science fiction and fantasy, one of the reasons that it has always been so close to my heart is it was the realm that sort of took the imagination the farthest fastest. You could be one chapter into something or one page into a comic book and light years, literally in some instances, away from wherever you were sitting in a way that seemed incredibly unique from other forms of storytelling and fiction.

Are there specific works that you remember from growing up that really inspired you or helped shape your career?

In the science fiction space, specifically, I was very early on an “Alien” acolyte, which for me is kind of horror and sci-fi fused. It’s like a haunted house movie in space. And, without getting too nerdy, all of the ancillary art that was generated as part of that movie and after its release became a huge wellspring of inspiration for me. Ray Bradbury and Stephen King were both, as a kid, huge influences as points of entry into the genre itself. With Ray Bradbury, it’s dizzying how he could spin secondary looks at the way in which we live our lives, or the way in which we utilize technology, in stories that are six to eight pages long.

Were you always a fan of comics? What were some of your favorites growing up?

I’ve been a comic book reader and lover my entire life, but the truth is that comics have changed a lot since I was a kid, and there’s just so much more now. There’s comics for everyone, and I didn’t necessarily find comics that were for everyone as a kid, so an awful lot of what I gravitated to were the most popular titles, because they were the most visible and the easiest to get your hands on in a small town. My biggest was “X-Men,” and not just because it was a huge franchise with a sprawling character base, but because there were so many different ways into that story, to that universe of stories. I’ve always liked those big universes in which I felt that there’s room for me to imaginatively participate, too.

“You could be one chapter into something or one page into a comic book and light years, literally in some instances, away from wherever you were sitting.”

How did you get into writing comics yourself and what were some of your first works?

The first several books that I did, either by myself or with partners, were very specifically ways of reimagining, reinventing, or rebooting movie ideas that we had started, so my first comic was reverse engineered from a screenplay that I had been repeatedly told, “It’s too big! I can’t see it! It’ll cost a billion dollars!” Ultimately, I realized in drawing comics, there really isn’t that sense of scale — drawing two people in a living room and drawing five people on an exploding spaceship costs the same. So, comics became a great proof of concept vehicle to leapfrog over the, “you can’t see it” — of course you can see it, it’s right here! In the process of it though, I discovered that my inner director, prop designer, wardrobe designer, and cinematographer hadn’t been serviced in my professional writing career for a really long time. With comics, I was getting to think about all that stuff. Not just the words and the spoken language, but the look and the design and the way swords looked or vehicles traveled. And it’s fun.

What do you like specifically about comics and graphic novels as a storytelling medium? What do you think they can accomplish that other mediums can’t?

First and foremost, I think most graphic novel and book readers come to books with more patience than they come to film and television content, so it can utilize that increased patience to convey stories that have more layers, more complexity, more nuance, that demand more thought and more independent contemplation. The way we read comic books is very unique. You’re reading the entire page, and also reading the first panel, and then also reading the splash. Just as a mechanism of compression, the amount of information that can be released in a short period of time is incredible in graphic novels. There are some graphic novels I’ve read where I’m two pages in and my head’s already spinning. It desaturates that pressure to handle the reader with kid gloves or to spoon feed them information, and it gives you permission to experiment in ways that I think are really exciting and good for storytelling in general. It’s one of the few environments in which you can tell big stories that still have the capacity to really surprise. In graphic novels, there’s so few rules. I’m allowed to do what I think is in the best service of the story or in destabilizing the reader in a way that’s incredibly robust.

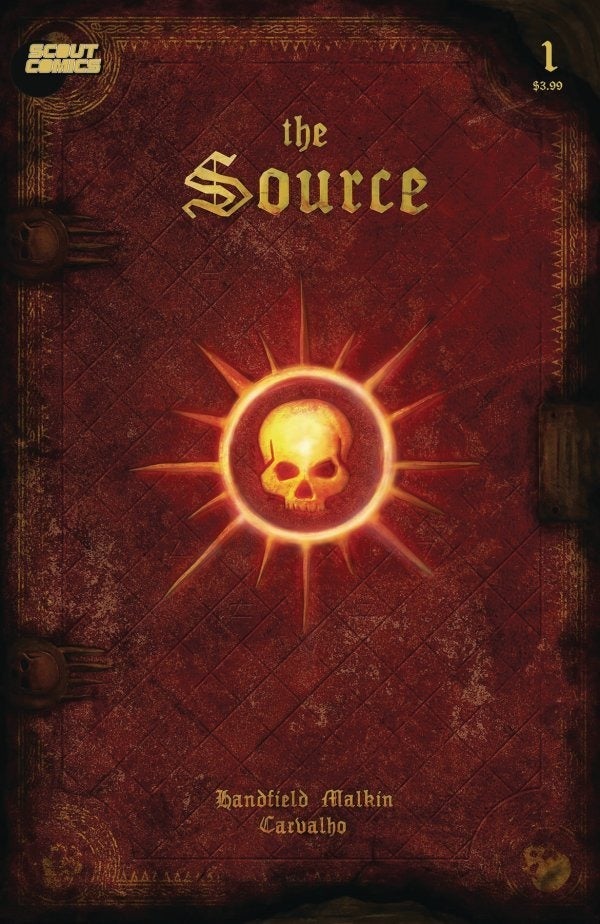

Can you talk about the comic series “The Source” that you co-authored?

“The Source” started as a screenplay that was preemptively damned as too big for its britches, and my writing partner and I set it up with an independent press called Scout Comics. It is essentially a story about magic as an exhaustible resource, much like oil or gas. A small-town high school physics teacher ultimately discovers real magic while conducting a series of experiments, and all these nefarious forces come out to find and persecute him because this has been hidden from humanity for eons, so it’s the story of his escape and his pursuit of figuring out what had happened. It did really well; we were Scout’s top-selling title for the first year of its release. It really grew past where it all started, taking on a life of its own, which is simply the best feeling. I really hope one day to return to that series.

“The Source” started as a screenplay that was preemptively damned as too big for its britches, and my writing partner and I set it up with an independent press called Scout Comics. It is essentially a story about magic as an exhaustible resource, much like oil or gas. A small-town high school physics teacher ultimately discovers real magic while conducting a series of experiments, and all these nefarious forces come out to find and persecute him because this has been hidden from humanity for eons, so it’s the story of his escape and his pursuit of figuring out what had happened. It did really well; we were Scout’s top-selling title for the first year of its release. It really grew past where it all started, taking on a life of its own, which is simply the best feeling. I really hope one day to return to that series.

What about your graphic novel — and upcoming movie — “Unikorn”? What’s the story behind that?

“Unikorn” was a passion project born right before the pandemic. My writing partner and I both happened to horribly have lost in-laws within the same two weeks. We have daughters the same age, and just talking about death with kids was … a fraught experience. Both of us go to Comic-Con every year, and there’s just much less content geared toward young girls. It struck us as a space that we wanted to fill, but we didn’t have a story. Then these deaths happened, so it became the story about a little girl who had lost a mother and a grandmother, and it was just a way of integrating a lot of what we had been talking about as both friends and parents into something that was fantastical. We were very lucky in that the manuscript for the book went out before the book was released, and it was optioned by Armory Films. They have since set it up at a studio called Stampede Ventures.

“Unikorn” was a passion project born right before the pandemic. My writing partner and I both happened to horribly have lost in-laws within the same two weeks. We have daughters the same age, and just talking about death with kids was … a fraught experience. Both of us go to Comic-Con every year, and there’s just much less content geared toward young girls. It struck us as a space that we wanted to fill, but we didn’t have a story. Then these deaths happened, so it became the story about a little girl who had lost a mother and a grandmother, and it was just a way of integrating a lot of what we had been talking about as both friends and parents into something that was fantastical. We were very lucky in that the manuscript for the book went out before the book was released, and it was optioned by Armory Films. They have since set it up at a studio called Stampede Ventures.

“It’s one of the few environments in which you can tell big stories that still have the capacity to really surprise.”

What other details can you share about the film at this stage?

Besides Stampede, the big attachment is the director. Her name is Debbie Berman, and this will be her first time directing a movie, but she is a world-class editor. She edited a bunch of Marvel movies — “Spider-Man: No Way Home,” “Captain Marvel,” “Black Panther” — so the idea is to bring her resources and some of the Marvel post-production magic to fore.

Can you talk about AMP Comics and your involvement?

It’s four of us, all of whom have our own backgrounds as both creators and screenwriters in various sectors. We believe in this model of trying to get film and television properties in comic form, where they can be protected. We really wanted to create a label that was creator centric, in which the creators of the content were participants in their IP moving forward. Ultimately, it’s a way of staying front and center in the comic-to-screen conversation.

What kinds of titles does AMP Comics publish?

It’s exclusively focused on fantasy, sci-fi, and horror. You want to be able to look at a logo and be like, “Oh, I know those types of stories.” And it’s the genre stuff that each of us know best. It’s what each of us have written. Just in terms of capitalizing on our strengths, doing exclusively genre content is a no-brainer, and I don’t see that changing. I don’t see us five years from now being like, “Finally. We’re so big, we can finally get into erotica.” I think we’re going to stay genre. Ultimately, genre stories tend to have the clearest high-concept hooks. They tend to be the most appropriate for adaptation. So, as a business model, it makes sense.

Are there any projects or titles you’re working on that you’re particularly excited about?

The one I’m writing right now that I’m most excited about is pure sci-fi. It’s very much spaceships and aliens and exotic alien planets. It’s called “Axon Infinity,” and it’s based on a novel that was written by a Sri Lankan neuroscientist. It’s about the chakras in neuroscience, but it’s imagining the chakras as extraterrestrial artifacts that this young team has to go on a quest to earn and collect. It’s sort of a “Star Wars”-esque story with young protagonists, but it’s ultimately about spiritual fulfillment, about a lot of the tenets of Eastern philosophy and religion that the author grew up with. It’s got a lot of layers — it’s about dimensions, and the human soul, and technology. It’s an overpacked sausage, and those tend to be my absolute favorite stories.