University of California, Riverside

Valley Truck Farms was once a rural refuge for Black families who built homes, gardens, and community just south of San Bernardino. Today, only a handful of houses remain, overshadowed by warehouses and surrounded by truck traffic. It’s a pattern that echoes across the region. Inland Southern California has become a hub for global commerce, but the costs to families, neighborhoods, and public health are mounting. Through a collaborative public history and art project called Live From the Frontline, researchers and residents are documenting the transformation — and toll — of supply chain communities in flux.

Built in 1928, St. Mark’s Missionary Baptist Church is now surrounded by warehouses. (Aerial footage of Valley Truck Farms by Tamara Cedré and Adrian Metoyer III, 2024, courtesy of the artists and A People’s History of the I.E.)

The “for sale” sign outside St. Mark’s Missionary Baptist Church belies the electricity that crackles inside the 97-year-old house of worship. Take a seat on one of the church’s 18 wooden pews, covered in plush, blood-red velvet, and you’re likely to count at least a handful of fascinators, jeweled brooches, and crisp pairs of gloves in the congregation. During more sedate stretches of the service, you might see paper hand fans wave lazily, rhythmically — that is, until the time comes to stand and sing and clap.

St. Mark’s was built in 1928, but it’s far from a time capsule. The church’s walls are lined with blown-up photographs of families: men in suits, women in dresses, babies on laps, older children arranged in height order like the bars of a xylophone. These are the Savilles, the Whites, the Overstreets, the Greens, and so many others who populated Valley Truck Farms, a once-thriving, predominantly Black community in San Bernardino for which St. Mark’s is one of the last remaining visible vestiges.

At its largest, the footprint of Valley Truck Farms covered about 1 square mile of southeastern San Bernardino and housed around 500 families. They began to trickle east, often from Los Angeles, in the latter half of the 1920s. The subdivided parcels of Valley Truck Farms offered these families the promise of land ownership, which was too often limited by discriminatory housing policies. Between the 1930s and ’70s, the population of Valley Truck Farms bloomed; residents not only built homes and grew their families but also cultivated the land, allowing for self-sufficiency and economic independence.

From Farmhouse to Warehouse: 1938-2025

Aerial maps of Valley Truck Farms from 1938, 1959, 1985, and 2025 illustrate the shift from a rural community to one now dominated by warehousing.

(Courtesy of Historic Aerials)

Percy Harper, who is only the fourth pastor in St. Mark’s near-century-long history, grew up in Valley Truck Farms and attended St. Mark’s as a congregant before becoming pastor in 1988. His mother and her family arrived in Valley Truck Farms from Arkansas in the 1940s by way of Los Angeles, part of the Great Migration of millions of Black Americans out of the South and into other corners of the United States that began in the early 1900s. Harper’s memories of Valley Truck Farms are colored by its entrepreneurial spirit; many residents grew food — namely corn, black-eyed peas, potatoes, tomatoes, and fruit trees — and raised livestock, including dairy cows, pigs, chickens, and turkeys.

Harper had planned to go to law school until he was in a serious car accident the day after graduating with his bachelor’s degree from UC Riverside in 1976. He describes waking up in the hospital as a critical turning point in his life, one that reoriented him back toward Valley Truck Farms and St. Mark’s. He assumed leadership of the church amid a period of gradual but dramatic transformation in the community.

Beginning in the late 1960s and ’70s, Harper says, local government officials quietly initiated a series of zoning changes in the area, redesignating land use from residential to commercial and reshaping neighborhood infrastructure to serve corporate interests rather than homeowners and families. Over time, the homes and gardens of Valley Truck Farms were replaced by a patchwork of warehouses; linger on the St. Mark’s stoop today and you’ll see warehouses across the street and shipping trucks on the roads. Harper doesn’t mince words; he describes the transformation of Valley Truck Farms into “an asphalt jungle of warehouses” as nothing less than “the undermining of a community.”

Paved Paradise

Paved Paradise

Many Bloomington homes and neighborhoods have been destroyed to make way for warehouses. (Aerial footage of Bloomington by Tamara Cedré and Adrian Metoyer III, 2024, courtesy of the artists and A People’s History of the I.E.)

What happened to Valley Truck Farms isn’t a rarity in Inland Southern California. In fact, the logistics industry has a long history in the two-county region, says Catherine Gudis, a public historian and professor of history at UCR, and a long history of transforming — or engulfing — communities that exist along the supply chain.

“Still, there’s a magic to this region,” Gudis says of the Inland Empire. “And it’s in part the people, and in part the landscape, and in part the way that industry and infrastructure frame so many of the views.”

Gudis is co-director of Live From the Frontline, a far-reaching “participatory memory” project of which St. Mark’s is one of a selection of Riverside and San Bernardino county sites spotlighted. The project marries archival research, oral histories and interviews with community members, original photography by artists from the region, documentary work, digital mapping, the creation of public and community-driven art installations, and partnerships with environmental justice organizations, all with a focus on exploring what Gudis describes as “the exploitation of land and labor” in the region.

Joining Gudis in the endeavor are co-directors Jennifer Tilton, chair and professor of race and ethnic studies at the University of Redlands, and Audrey Maier, public history director of the Civil Rights Institute of Inland Southern California and a 2021 graduate of UCR’s doctoral program in public history. Maier’s own family roots in the Inland Empire community of South Colton, known for its leading role in cement production throughout much of the 20th century, extend across five generations.

From left: Audrey Maier, Catherine Gudis, and Jennifer Tilton, co-directors of the Live From the Frontline project, outside St. Mark’s in June. (UCR/Stan Lim)

“With Live From the Frontline, we wanted to show these different areas that are all connected through logistics, and these long histories of what we call the ‘slow violence of the supply chain,’ and work with the individual communities to flesh out their unique stories but also to connect them all together,” Maier says of the project, which developed out of a larger archival and mapping initiative the historians continue to collaborate on called A People’s History of the I.E. “We want these different communities to find shared similarities and histories through the project and connect through those.”

“With Live From the Frontline, we wanted to show these different areas that are all connected through logistics, and these long histories of what we call the ‘slow violence of the supply chain.’”

— Audrey Maier

Over the past several years, working on the project has seen Gudis, Tilton, and Maier become embedded in communities — like South Colton, Mira Loma, and Fontana — where decades of industrialization and commercialization have resulted in massive labor shifts as well as environmental pollution, some of the worst air quality in the country, and high rates of asthma and other respiratory illnesses.

A Heavy Burden

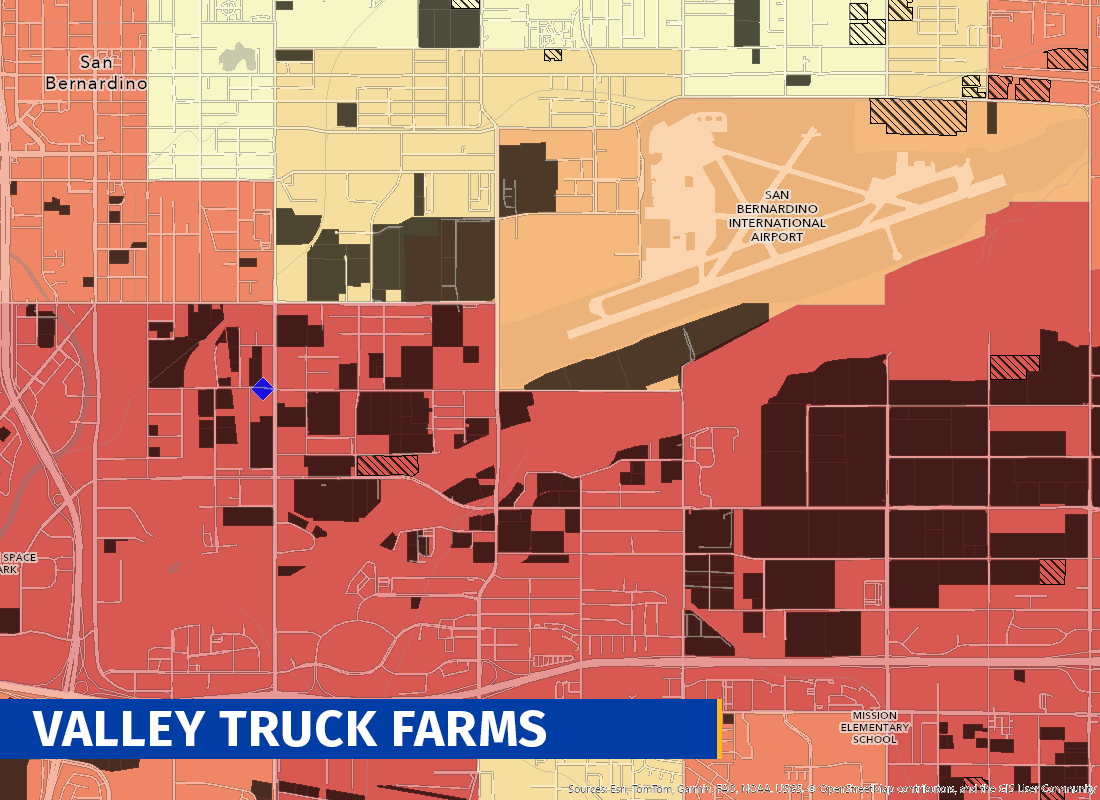

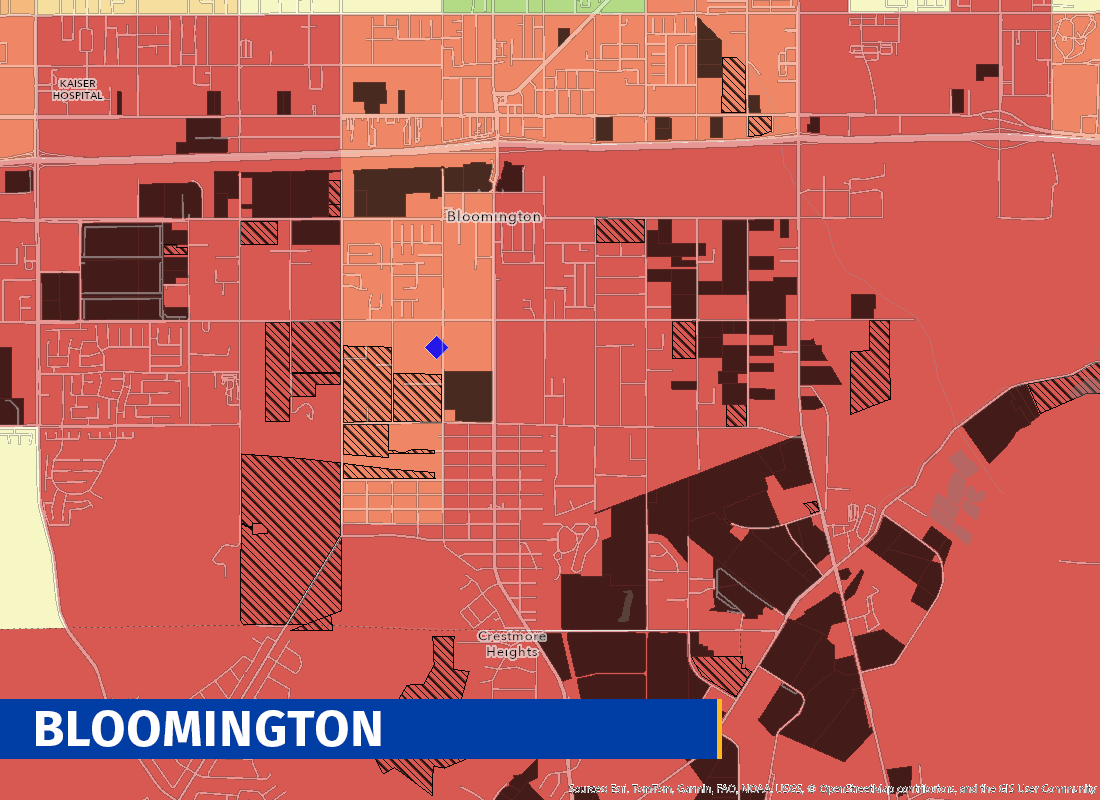

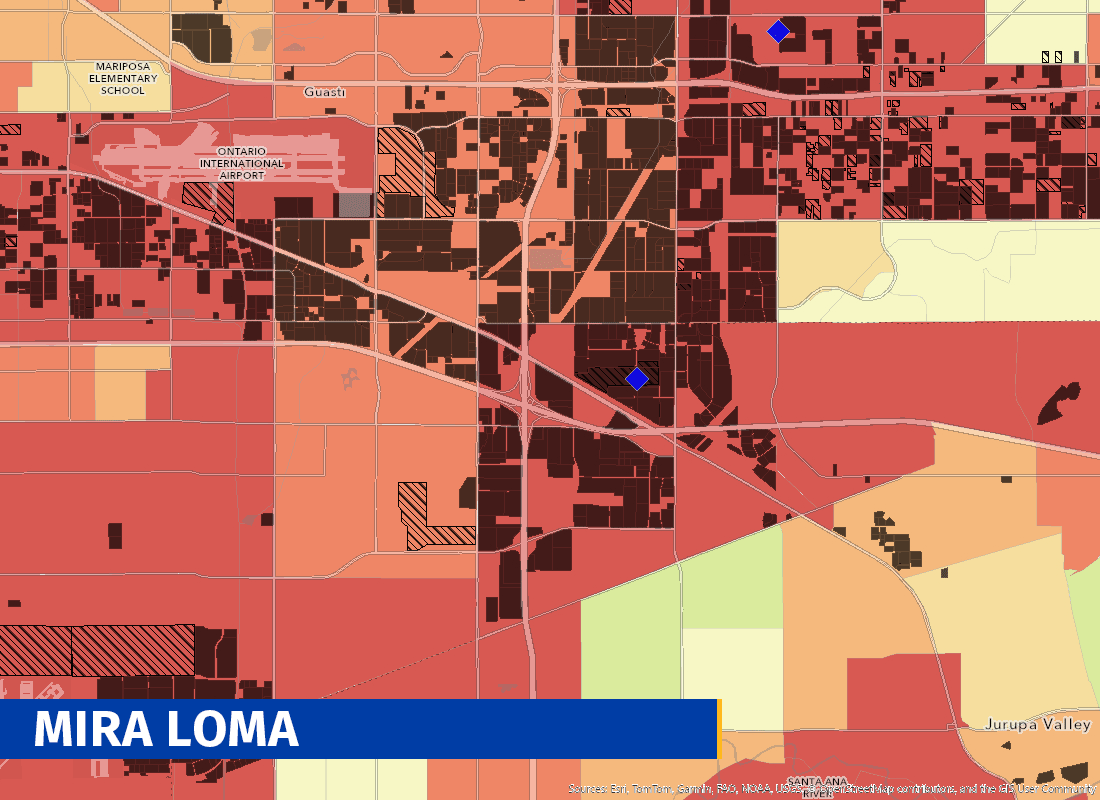

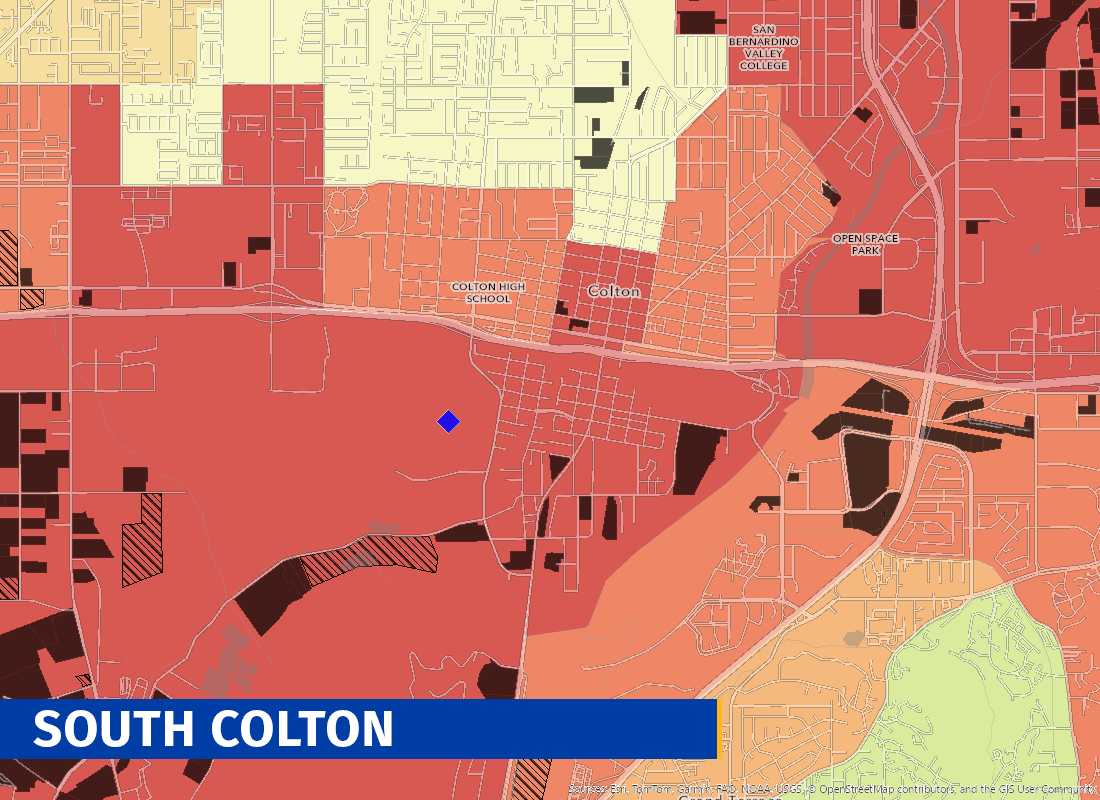

Decades of industrialization in Inland Southern California communities including Valley Truck Farms, Bloomington, Mira Loma, and South Colton have resulted in some of the worst air quality in the country.

(Maps created by Jennifer Tilton and Lane Eppenberger using Warehouse CITY Data Layers and CalEnviroScreen 4.0)

Pollution Burden Percentile

Their project also seeks to track places as they change in real time; one example is unincorporated Bloomington, a rural, ranch-friendly community just west of Colton whose population has skewed heavily Latino and working class for the past 50 years. Since 2022, the ongoing development of an industrial park in Bloomington has resulted in a community interrupted, with some homeowners accepting deals to vacate their land and others seeking to stay in place even as the neighborhood becomes increasingly unlivable.

Bloomington: Past, Present, and Future

Bloomington has seen a rapid expansion of warehousing from 2004 to 2024 (gray regions), with even more areas zoned for development in the near future (striped regions).

(Aerial Maps created by Lane Eppenberger using Warehouse CITY Data Layers, ESRI Wayback Imagery, and aerial imagery from 2004, courtesy of UCSB Library Geospatial Collection)

As part of the project, Gudis, Tilton, and Maier partnered with local artists, led by visual artist Tamara Cedré, who photographed and produced multimedia pieces about many of the Live From the Frontline sites and community members. The opportunity to collaborate with artists was a welcome one, Gudis says, made possible through grant funding awarded by Creative Corps Inland SoCal, an initiative financed by a constellation of organizations including the California Arts Council.

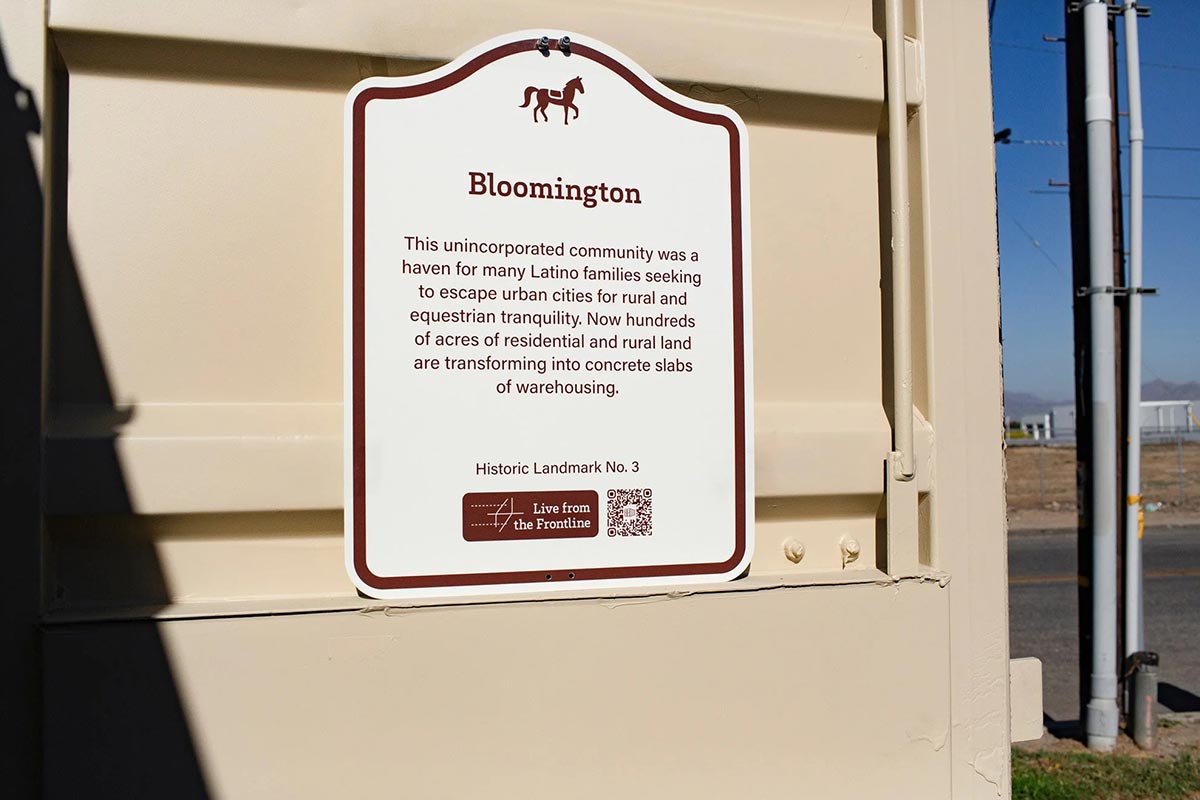

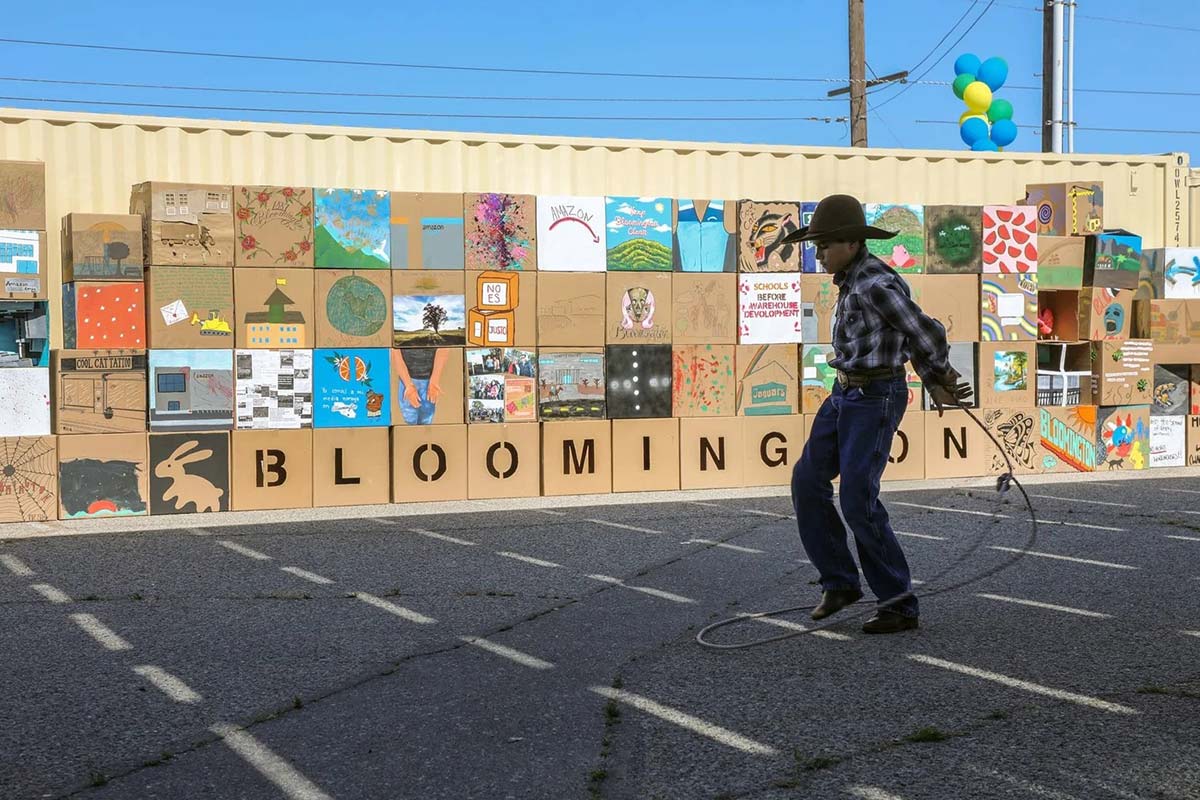

Among the site-specific installations produced by the Live From the Frontline team is “Bloomington Speaks: A Community Sculpture & Art Exhibition at Zimmerman Elementary School”; at the June 2024 event, community members were invited to express their feelings about warehousing and Bloomington’s transformation by decorating cardboard shipping boxes. The boxes were then displayed outside a shipping container in the parking lot of Zimmerman Elementary School, which is in the process of being relocated from its current site within the borders of the planned industrial park.

Visitors look at the images and text displayed inside a shipping container as part of the “Bloomington Speaks” art installation. (Photo by Tamara Cedré, 2024, courtesy of the artist and A People’s History of the I.E.)

Signage on the shipping container at the “Bloomington Speaks” art installation acknowledges the history and reshaping of the once rural community. (Photo by Tamara Cedré, 2024, courtesy of the artist and A People’s History of the I.E.)

A boy swings a lasso in front of cardboard boxes decorated by community members as part of the “Bloomington Speaks” art installation. (Photo by Josue Munoz, 2024, courtesy of the artist and A People’s History of the I.E.)

The New Company Towns?

The New Company Towns?

Amazon warehouses now occupy the site of the former Mira Loma Space Center. (Aerial footage of Mira Loma Village and warehouses by Tamara Cedré and Adrian Metoyer III, 2024, courtesy of the artists and A People’s History of the I.E.)

Southwest of Bloomington and within the municipal borders of Jurupa Valley, Mira Loma can be considered “ground zero” for the supply chain in Inland Southern California, Gudis says. The area’s vineyards, now mostly extinct, once produced the largest output of any grape-growing region in California. By World War II, however, Mira Loma’s proximity to railways and highways made it a desirable host for military supply operations, including those established to furnish the Manzanar War Relocation Center, where more than 10,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated and incarcerated several hours north at the base of the Sierra Nevada mountains.

“The clear precedents for warehouses in the region have to do with the wartime efforts to create military bases and to generate jobs that related to those bases,” Gudis says, again emphasizing the region’s prime proximity to rail and freeway corridors. “Industry was connected not just to those military elements, but the discussion was always around the transportation infrastructure and large expanses of available land. World War II was like a linchpin because there was major growth using infrastructure. That’s when the biggest warehouses began.”

Vineyards once spanned from Mira Loma to Rancho Cucamonga, occupying over 20,000 acres by 1917. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The U.S. Army established the Mira Loma Quartermaster Supply Depot in 1942, relying on civilian women, who made up 80% of the workforce. (c. 1943, Alvin P. Stauffer, Historical Section, Office of the Quartermaster General)

After World War II, Gudis says, the region hungrily courted industry, over time transitioning from production — of citrus in Riverside’s Eastside neighborhood, cement in South Colton, and steel in Fontana, among other outputs — to the movement and storage of goods. In 1956, Riverside County began to allow industrial waste dumping at Jurupa Valley’s Stringfellow Acid Pits; by the early 1980s, the site was considered one of the most toxic places in California. And along the way, the military invested heavily in the Inland Empire, growing the March and Norton Air Force bases throughout the mid-20th century until they were realigned in the early 1990s, with March significantly downsizing and Norton closing entirely.

“There were economic pundits who really led the region in claiming that warehousing was the only way to go because the land was cheap, and the labor was cheap — selling out the working people of the region.”

— Catherine Gudis

“After the bases realigned, there was even more land available,” Gudis says. “In the early 2000s, when the region was so financially strapped, there were economic pundits who really led the region in claiming that warehousing was the only way to go because the land was cheap, and the labor was cheap — selling out the working people of the region. And, at least from what we’ve found, it’s much easier for developers to get commercial industrial zoning in unincorporated areas because county supervisors — who approve rezoning — answer to many localities across a really big geographical area, and there’s a broader base for seeking out anything that could possibly add to county income.”

The 101 homes in Mira Loma Village are surrounded on all sides by warehouses. (Photo by Aaron Glascock, 2022, courtesy of A People’s History of the I.E.)

An aerial view of Mira Loma. (Photo by Eduardo Gonzalez, 2024, courtesy of A People’s History of the I.E.)

Out of the Box

Out of the Box

The destruction of Colton’s natural landscape laid the groundwork for more than a billion square feet of distribution warehouses in the Inland Empire and the tens of thousands of trucks and trains that serve them daily. (Aerial footage of Colton trains alongside the I-10 freeway by Tamara Cedré and Adrian Metoyer III, 2024, courtesy of the artists and A People’s History of the I.E.)

Today, warehousing continues to expand throughout Inland Southern California into communities like Mead Valley, Barstow, and Hesperia. Gudis, Tilton, and Maier don’t yet see an end in sight to their Live From the Frontline project, and hope to coordinate more installations, events, and collaborations in support of regional environmental justice organizations such as the People’s Collective for Environmental Justice and the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice.

“The promise of jobs in 5 or 10 years may evaporate, and then we’ll have huge blocks of land providing almost no jobs but all the environmental burdens.”

— Jennifer Tilton

Though the researchers admit it can be difficult for communities to push back against industry’s encroachment, they say they have observed some success among residents who have banded together to collectively resist lowball offers for their properties, for example, and demand higher compensation per square foot from developers. Another cause for hope, according to Gudis: the creation of San Bernardino Airport Communities, a coalition of community members, labor unions, environmental justice groups, and faith-based organizations that, in 2023, managed to halt the Airport Gateway Specific Plan, which would have rezoned nearly 700 acres of land in San Bernardino and Highland for industrial use.

“You can see communities trying to learn lessons from each other as they have faced these struggles, and to me, that’s really powerful,” Tilton says.

Moving forward, communities will need to advocate for labor regulations that ensure more sustainable jobs, the researchers agree.

“Communities are sold on the promise of all these new jobs that warehousing and the logistics industry will bring, but these are exactly the robot-replaceable jobs, right?” Tilton says. “The promise of jobs in 5 or 10 years may evaporate, and then we’ll have huge blocks of land providing almost no jobs but all the environmental burdens.”

In this case, advocacy begins with education. Gudis, Tilton, and Maier emphasize that one of their biggest aspirations for the project is for its various materials to be incorporated into local K-12 ethnic studies curricula — something they’ve been told by area teachers has already begun to happen. The goal is to show the region’s young people that history is relevant, that change doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and that they can impact decisions about things like the growth of the logistics sector in their communities.

“We really want to question: how it got here, why it’s here, and do we want it here?” Maier says. “And if we don’t, what’s something else that we can put in its place?”